I stayed in a hall of residence last night. One of those accommodation blocks with the aesthetic of a budget hotel, but the vibe of a holding cell. Single bed. Thin mattress. Window that lets in zero air but all the noise. The kind of place that has a fire safety poster from 2004 and a light that buzzes like it resents being switched on.

And the door. That door.

It locked. Technically. But it did not make me feel safe. It didn’t have the weight or the resistance or the reassuring click of something built to keep danger out. It felt flimsy. Like a door that would apologise while being kicked in.

So I did what I always do when I’m alone, in a strange room, in a strange building, surrounded by strangers.

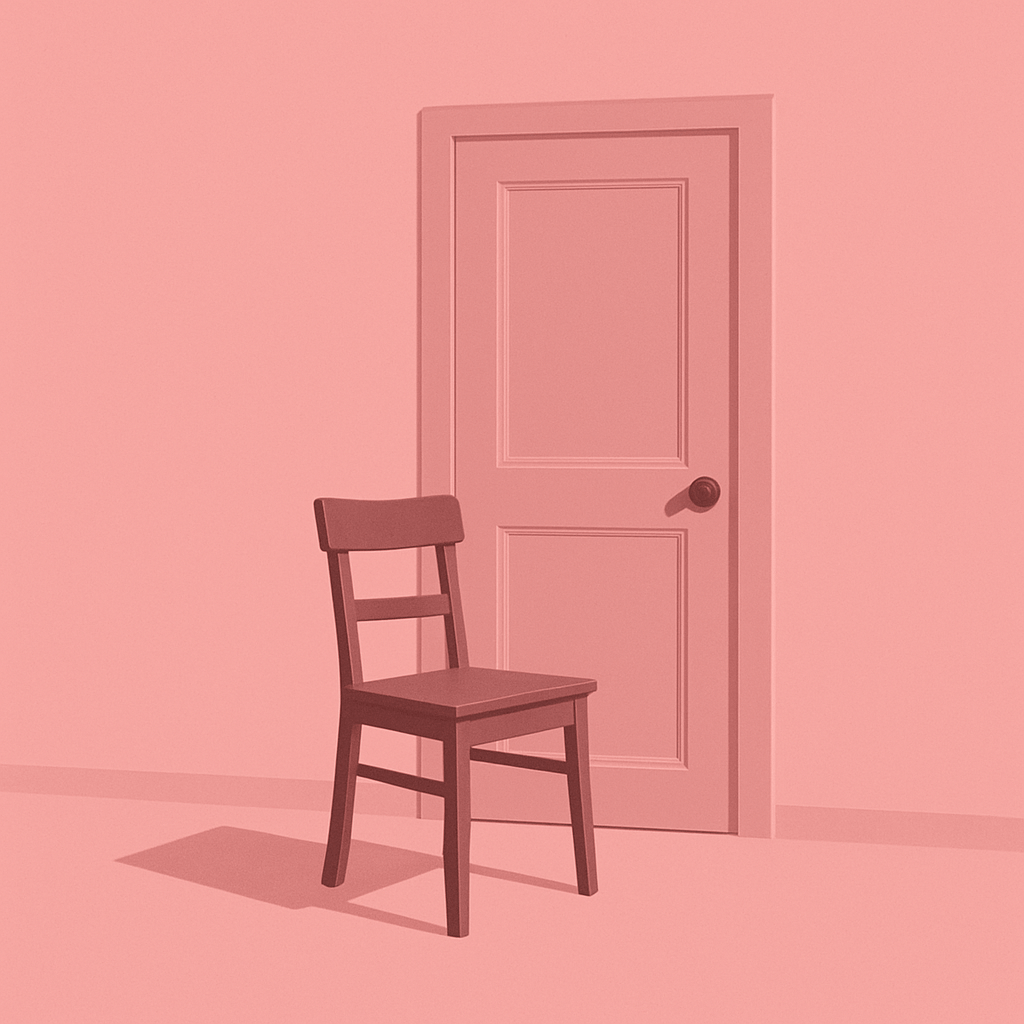

I put a chair in front of the door.

Not wedged. Not barricaded. Just placed. A symbolic gesture. Like a toddler offering you a stick to protect yourself from a bear. It would not have stopped anyone. But it was something. And sometimes that’s all your brain is looking for. A gesture. A tiny attempt at control. A little theatrical ritual for the benefit of your nervous system.

That chair meant nothing. And yet it meant everything.

It was the first thing I thought about when I put my bag down. It was the last thing I looked at before I turned out the light.

And I know, objectively, it looks ridiculous. I know most people walk into a hotel room or student hall and just… exist. They don’t scan the locks. They don’t plan their exit. They don’t mentally prepare to be attacked in the night.

But some of us do.

I only know one other person who puts something in front of the door like this. He’s a man. He doesn’t have obvious trauma either. But he gets it. He gets the way fear doesn’t always wait for a logical reason. The way your brain sometimes wires itself for danger because it learned early that being caught off guard is worse than living in a constant state of threat.

For me, there is trauma. There is paranoia. But I don’t know exactly where it started.

I remember being fourteen. A boy, he was sixteen, grabbed me in the street. He worked at the paper shop where I did my deliveries. I already knew his name. I knew who his brothers were. One of them I would see around Manchester years later. I saw the boy again too. More than once. Just out and about, like nothing happened.

It didn’t become anything violent. He didn’t assault me. But it was a moment. And I carried it.

I don’t know if it was my mum who rang the shop or someone else, but later he turned up at the house to apologise. With his mother. I wasn’t in. I don’t know how that conversation went. I only know it happened. And that it didn’t undo anything.

That incident wasn’t the major trauma. It wasn’t the thing that broke the dam. But it planted something. A feeling. A low, simmering message that said, “You’re not safe.” A hint of warning that stayed with me.

I can’t say when the paranoia really set in. I remember one morning screaming because the shed door hit my shoulder and I thought it was a person. I remember sitting in silence with vivid, unwanted images of people I loved turning on me. Not because they were violent. Not because I believed they would hurt me. Just because my brain had started running threat simulations at full speed.

This isn’t dramatic. It’s just how some of us live.

I have shoes by the bed. Keys within reach. Phone charged. Curtains shut tightly. My body often facing the door. My whole life arranged in ways that most people never notice. But for me, it is constant. It is exhausting. It is boring and relentless and invisible.

If you are someone who recognises this, you are not alone. You are not weak. You are not weird. You are surviving. You are adapting.

How You Can Help When You Don’t Get It

If you don’t understand why someone puts a chair in front of the door or has a routine that seems “odd,” here’s the deal: you don’t need to get all the details. You don’t need to know their entire trauma history or have perfect empathy on tap. But you can choose to believe them.

Don’t laugh. Don’t question or dismiss their fear. Don’t call them paranoid or dramatic.

Instead, ask what they need. Offer your presence. Let them do their thing even if it seems pointless to you.

Sometimes the best help is just saying, “I see you. I’m here.”

Fear is not always born from violence. Sometimes it is born from the possibility of it. From the threat. From the fact that something happened once and it could happen again. From the feeling that your body is not yours, not really, not when the world can grab it, apologise, and move on.

So yes, I placed a chair in front of the door.

It wasn’t to stop anyone. It wouldn’t have. It was to create a feeling. The feeling that maybe, just maybe, I was less alone in that room. That I had done something, however pointless, to try and hold the line.

I know how it looks.

It looks paranoid. It looks excessive. It looks like I don’t trust the world.

That’s because I don’t.

And to be perfectly honest, the world hasn’t done a great job of earning it.

If this resonates

If any part of this sounds familiar, if you put chairs in front of doors, or scan exits in cafés, or go stiff when someone walks behind you in the dark, you are not broken. You are trying to stay alive in a world that made you feel unsafe.

If you’re in the UK and want to talk to someone:

Mind | 0300 123 3393 | https://www.mind.org.uk

Samaritans | 116 123 (free, 24/7)

Rape Crisis England & Wales | 0808 802 9999 | https://rapecrisis.org.uk

You don’t need a visible wound. You don’t need a headline trauma. If it hurts, it matters.

And if your safety routine involves a chair in front of the door?

Welcome. You’re among the cautious, the prepared, the quietly brilliant.

You’re not paranoid.

You’re paying attention.

Leave a comment